Young Mickey Rourke: Before the chiseled, weathered face, the whispered tales of boxing rings and Hollywood exile, there was a different Mickey Rourke. In the early 1980s, he erupted onto the screen not as a caricature of lost glory, but as its very embodiment—in the making. He was a new kind of leading man, a raw nerve of vulnerability and danger that the film industry hadn’t quite seen before. To talk about the actor today is to inevitably discuss his remarkable, Oscar-nominated comeback in “The Wrestler.” But to truly understand the mythos of Mickey Rourke, one must journey back to the beginning, to the era of the young Mickey Rourke, when he wasn’t a comeback story but the next big thing. He was a beautiful, brooding paradox, an actor of such intense sensitivity and unpredictable edge that he seemed to hold the entire future of American cinema in his hands. This is the story of that moment, a celebration of the prodigious talent that was, and an exploration of the promise that flickered so brilliantly before the storm.

The young Mickey Rourke was more than just an actor; he was a cultural phenomenon. He represented a shift away from the clean-cut heroes of the past and the disco-era smoothness of the late 70s. In his place was a streetwise poet, a man who looked like he’d just stepped out of a barroom brawl but could articulate the deepest of human sorrows. His performances were not merely acted; they were lived. He immersed himself so completely in his roles that the line between Rourke and the character often blurred, both for the audience and, most tellingly, for the actor himself. This article will delve deep into the films that defined this electrifying period, from his scene-stealing turn in “Body Heat” to his iconic roles in “Diner,” “Rumble Fish,” “9 1/2 Weeks,” and “Angel Heart.” We will explore the unique alchemy of his Method acting approach, his complicated relationship with fame, and the personal demons that both fueled his art and, ultimately, led him away from it. The legend of the young Mickey Rourke is a tale of what was, what could have been, and why his brief, incandescent reign in the 80s continues to captivate us decades later.

The Making of a Maverick: Early Life and Influences

To understand the artistry of the young Mickey rourke young on screen, one must first look at the streets that forged him. Born Philip Andre Rourke Jr. in Schenectady, New York, and raised primarily in Miami, his childhood was far from the Hollywood glitz he would later both embrace and reject. His early life was marked by tumult and a search for identity. His parents divorced when he was young, and his mother eventually remarried, a relationship that by all accounts was fraught with conflict. This unstable home environment pushed the young boy outward, onto the streets and into a world where toughness was a currency and survival was a skill. It was here that he first found an outlet in boxing, a discipline that provided both a refuge and a channel for the anger and confusion he carried inside. The boxing ring became his first stage, a place where performance and pain were inextricably linked.

This background is not merely a biographical footnote; it is the bedrock of his entire persona. The boxer’s swagger, the wary eyes, the sense of a man who had seen too much too soon—all of it was authentic. When he eventually turned to acting, studying at the famed Actors Studio, he didn’t leave this past behind; he weaponized it. The Method acting techniques he absorbed, championed by legends like Lee Strasberg, demanded an emotional truth drawn from the actor’s own experiences. For the young Mickey Rourke, this was a perfect fit. He had a deep well of personal hardship to draw from, and he used it to create characters that felt startlingly real. His wasn’t a performance of learned lines and blocked movements; it was an excavation of his own soul, projected onto the characters he played. This fusion of street-honed instinct and rigorous Method training created an actor unlike any of his contemporaries, one who could be both brutally physical and heartbreakingly tender, often within the same scene.

The Ascent Begins: Scene-Stealing Turns in “Body Heat” and “Diner”

Every great actor has that moment, the cinematic equivalent of a lightning strike, where the industry and the audience sit up and take notice. For the young Mickey Rourke, this happened not with a leading role, but with two supporting performances that showcased the incredible range he possessed from the very start. The first was in Lawrence Kasdan’s steamy neo-noir “Body Heat” (1981). In a film filled with duplicitous and lustful characters, Rourke played Teddy Lewis, a smarmy, low-level arsonist. It’s a small part, but in the hands of the young Mickey Rourke, it becomes unforgettable. With his slicked-back hair, a constant smirk, and an air of casual corruption, he steals every scene he’s in. He wasn’t just playing a criminal; he was embodying a specific type of greasy, Florida-man charm that felt utterly authentic. It was a flash of brilliance, a promise of a major new character actor in the making.

The very next year, he delivered a performance that was its polar opposite, proving his versatility was his greatest strength. In Barry Levinson’s beloved ensemble piece “Diner” (1982), Rourke was Robert ‘Boogie’ Sheftell. Boogie is the group’s resident handsome gambler and charmer, a man seemingly all surface-level cool. Yet, the young Mickey Rourke infused him with a profound, underlying sadness. Watch the scene where Boogie, in a moment of quiet desperation, glues his eyebrows back on after shaving them for a bet. It’s a hilarious moment, but Rourke plays it with a tragicomic vulnerability that reveals the fragile ego and deep-seated insecurity beneath the suave exterior. This ability to hint at the darkness within the golden boy, or the humanity within the thug, set him apart. While his “Diner” castmates—Kevin Bacon, Daniel Stern, Steve Guttenberg—were excellent, it was Rourke who felt the most unpredictable, the most modern, the most like a real person caught on film. These two roles, back-to-back, announced the arrival of a major talent, an actor who could not be easily categorized.

Leading Man Intensity: “Rumble Fish” and the Coppola Collaboration

If “Body Heat” and “Diner” were the opening acts, then Francis Ford Coppola’s “Rumble Fish” (1983) was the moment the young Mickey Rourke truly ascended to the stratosphere of acting greats. Coppola, a master filmmaker, saw in Rourke a unique and potent star quality, casting him as The Motorcycle Boy, the near-mythic older brother to Matt Dillon’s Rusty James. The film, shot in stark black and white with expressionistic flair, is a poetic and moody meditation on hero worship and time. And at its center is Rourke’s performance, a work of breathtaking subtlety and quiet power. The Motorcycle Boy is weary, philosophical, and colorblind in a world he perceives as shades of gray—a metaphor for his disconnection from a reality that feels too small for his spirit. Rourke plays him with a haunting, almost ethereal stillness.

This performance is a masterclass in saying everything by saying very little. The young Mickey Rourke communicates The Motorcycle Boy’s inner turmoil through his posture, his distant gaze, and a voice that is little more than a world-weary whisper. He is less a street gang leader and more a tragic poet king, aware of his own doomed fate. The collaboration with Coppola was a meeting of two artistic souls, both willing to take big, stylistic swings. Coppola gave Rourke the space to build a character from the inside out, and Rourke delivered what many consider his first truly iconic performance. It was a role that cemented his status not as a mere actor, but as an artist. He wasn’t just playing a part; he was channeling a state of being. The critical acclaim for his work was universal, and it solidified the notion that the young Mickey Rourke was the most exciting and profound actor of his generation, a successor to the Brandos and Deans of a bygone era.

Redefining Eroticism and Controversy: “9 1/2 Weeks” and “Angel Heart”

By the mid-1980s, the young Mickey Rourke was not just a critical darling; he was a full-blown movie star. And with that stardom came roles that pushed the boundaries of mainstream cinema, both in terms of erotic content and psychological horror. The first of these was Adrian Lyne’s “9 1/2 Weeks” (1986), a film that, upon its release, was both a scandal and a commercial success. Rourke plays John, a wealthy, mysterious Manhattanite who enters into a intense, psychosexual relationship with Elizabeth, played by Kim Basinger. The film is a symphony of sensuality built on power dynamics, obsession, and surrender. The young Mickey Rourke is the engine of this dangerous allure. His John is controlled, enigmatic, and dangerously charismatic. He doesn’t need to raise his voice; his quiet commands and intense stare are enough to captivate both Basinger’s character and the audience.

The film’s infamous scenes—the blindfolded food tasting, the wardrobe montage—are iconic because of Rourke’s committed performance. He makes the character’s controlling nature not just monstrous but strangely compelling. He was the perfect actor for the role, bringing a raw, animalistic sexuality that was light-years away from the safe, romantic leads of the time. Immediately following this, he dove into the depths of the occult with Alan Parker’s “Angel Heart” (1987). As Harry Angel, a seedy private investigator descending into a hellish mystery in New Orleans, the young Mickey Rourke delivered a performance of mounting paranoia and sheer terror. The film’s climax is a masterstroke of psychological horror, and it works entirely because of Rourke’s journey. We see his cynical, street-smart detective slowly unravel, his bravado stripped away to reveal pure, primal fear.

Table: Defining Films of the Young Mickey Rourke Era (1981-1987)

| Film Title | Year | Director | Role | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body Heat | 1981 | Lawrence Kasdan | Teddy Lewis | Scene-stealing supporting role; showcased early charisma and menace. |

| Diner | 1982 | Barry Levinson | Robert ‘Boogie’ Sheftell | Revealed deep vulnerability and cemented his status as a premier ensemble player. |

| Rumble Fish | 1983 | Francis Ford Coppola | The Motorcycle Boy | Iconic, poetic performance; collaboration with a major auteur. |

| The Pope of Greenwich Village | 1984 | Stuart Rosenberg | Charlie Moran | Perfect blend of street-smart ambition and tragic loyalty. |

| 9 1/2 Weeks | 1986 | Adrian Lyne | John | Redefined the erotic thriller; made him an international sex symbol. |

| Angel Heart | 1987 | Alan Parker | Harry Angel | Masterclass in psychological horror and descent into madness. |

| Barfly | 1987 | Barbet Schroeder | Henry Chinaski | Immersive portrayal of poet Charles Bukowski; critical acclaim. |

These two films, “9 1/2 Weeks” and “Angel Heart,” represent the peak of his commercial and artistic power. He was choosing challenging, often controversial material and fearlessly committing to it. He was unafraid to be unlikeable, mysterious, or downright terrifying. This period solidified the unique duality of the young Mickey Rourke: he was a sex symbol who explored the dark side of desire, and a leading man who was willing to take his audience to the brink of hell.

Katie Price Young: The Making of a Modern Icon and the Person Behind the Persona

The Method and the Mayhem: Inside Rourke’s Process

The performances of the young Mickey Rourke were so potent because they felt less like acting and more like possession. This was no accident; it was the direct result of his devout commitment to Method acting, a technique that encourages actors to draw upon their own emotions and memories to create a character. For Rourke, this wasn’t a part-time job; it was a total immersion. He would famously stay in character for the entire duration of a film shoot, both on and off set. This meant that the brooding, silent intensity of The Motorcycle Boy or the dangerous allure of John from “9 1/2 Weeks” wasn’t just for the cameras; it was who he was for months at a time. This approach created an unparalleled authenticity on screen, but it also came at a great personal cost and often created tension on his film sets.

Stories of his process are the stuff of Hollywood legend. For “Rumble Fish,” he reportedly learned how to play the harmonica flawlessly for a single, brief scene. For “The Pope of Greenwich Village” (1984), he spent weeks with small-time hustlers in New York to perfect his character’s accent and mannerisms. His dedication to the gritty, semi-autobiographical “Barfly” (1987), where he played Henry Chinaski, the surrogate for poet Charles Bukowski, was total. He lived in fleabag hotels and immersed himself in the skid row lifestyle to understand the character’s despair and defiant joy. This absolute surrender to his roles is what made the young Mickey Rourke so electrifying to watch. Audiences could sense they were not watching a performance, but a piece of a man’s soul. However, this same intensity often alienated directors and co-stars. His unwavering commitment to his own process sometimes clashed with the practical demands of filmmaking, planting the early seeds of his reputation as being “difficult,” a label that would follow him and contribute to his eventual exile from the industry he once seemed destined to rule.

The Turning Point: When the Shine Began to Fade

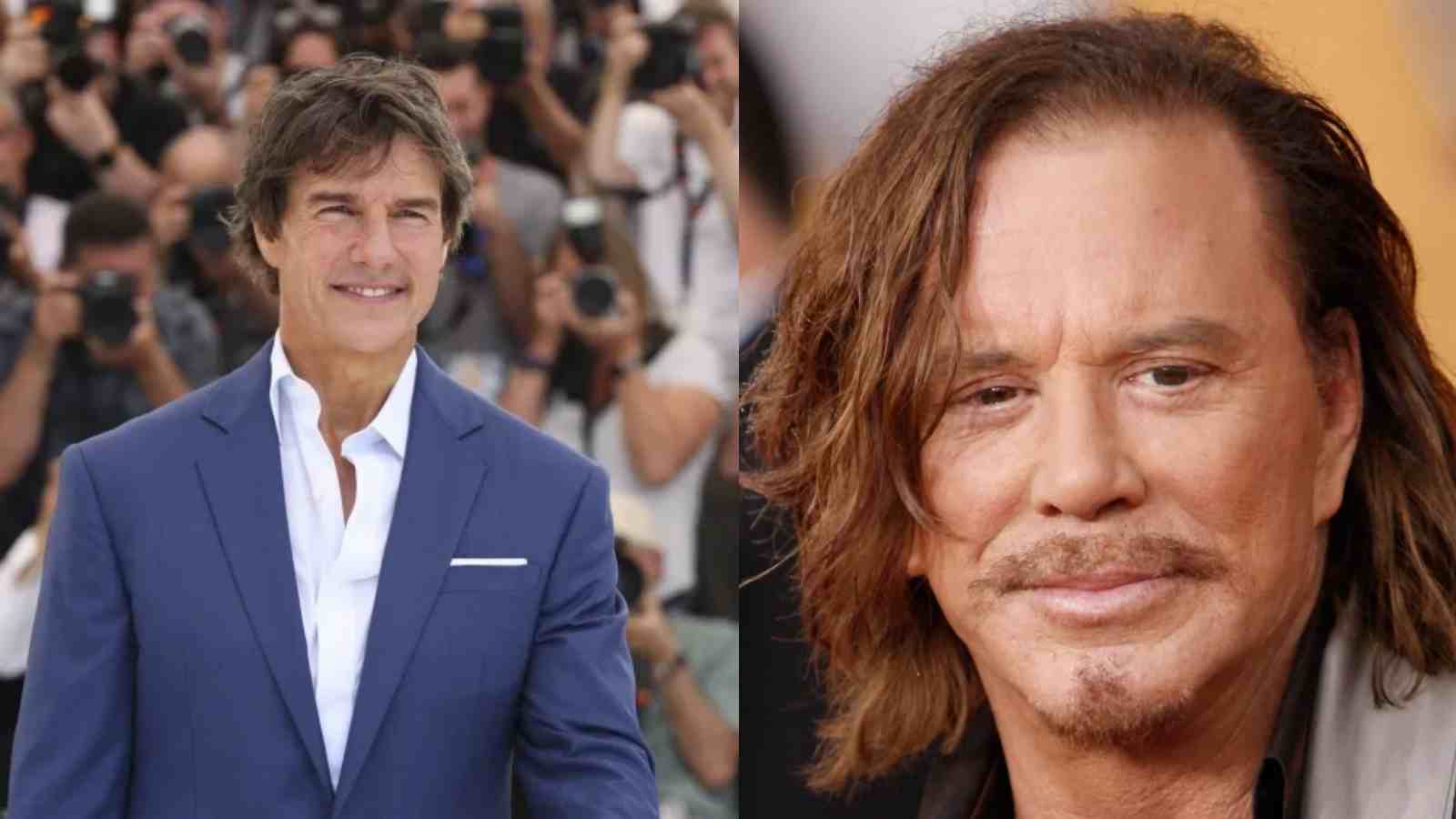

The trajectory of a star is rarely a straight line upward, and for the young Mickey Rourke, the incredible momentum of the early-to-mid-80s began to stall as the decade drew to a close. A combination of factors led to this turning point. First, there was his infamous pickiness with roles. He was known for turning down parts that would become iconic for other actors, a list that is staggering in hindsight. He passed on leads in “Beverly Hills Cop,” “Platoon,” “Top Gun,” and “Rain Man,” among others. His reasons varied—disinterest in commercial fare, clashes with directors, or a simple gut feeling—but the cumulative effect was that he ceded his place at the top of the A-list to others. He was following his artistic compass, but that compass often pointed away from mainstream success.

Secondly, the very Method intensity that made his performances so brilliant began to wear on the Hollywood system. Directors who were initially eager to work with the brilliant young Mickey Rourke found the reality of his process—the stubbornness, the staying in character, the emotional volatility—to be exhausting and counter-productive. The stories that once painted him as a dedicated artist were slowly being reframed as tales of a troublesome liability. Furthermore, his personal life was becoming increasingly chaotic. His passion for boxing resurfaced, not as a hobby, but as a professional pursuit. He felt a need to return to the ring, to resolve unfinished business from his youth. This decision, viewed by the industry as bizarre and self-destructive, marked the beginning of the end of his first act. The beautiful, nuanced actor was willingly subjecting his face and body to the brutal punishment of the sport, seemingly turning his back on the gift that had made him famous. The promise of the young Mickey Rourke was slowly being eclipsed by the reality of a man at war with himself and the world that adored him.

The Legacy of the Young Mickey Rourke

So, why does the specter of the young Mickey Rourke continue to loom so large in our cultural memory? His time at the pinnacle was relatively brief, a dazzling five- or six-year window. Yet, the impact of his work during that period is immeasurable. He redefined what a leading man could be. Before him, male movie stars were largely expected to be heroic, dependable, and emotionally accessible. The young Mickey Rourke introduced a new archetype: the beautiful wreck, the sensitive brute, the man who was as likely to cry as he was to throw a punch. He brought a gritty, downtown New York sensibility to mainstream cinema, an aura of authentic street culture that felt dangerous and exciting. His influence can be seen in a generation of actors who followed, from Brad Pitt’s early, feral roles to Joaquin Phoenix’s penchant for internal, troubled characters.

“I think I was a better actor then because I wasn’t trying to prove anything. I was just being.” — A reflection often attributed to Rourke on his early career.

The legacy of the young Mickey Rourke is not just in the films he left behind, but in the path he carved. He proved that vulnerability was not a weakness but a profound strength in a performance. He demonstrated that sexuality on screen could be complex, dark, and unsettling, yet utterly compelling. His work in “Diner,” “Rumble Fish,” and “Angel Heart” remains a masterclass for aspiring actors, a textbook on building a character from the inside out. The tragedy, of course, is that the trajectory was not sustained. The subsequent decades of professional boxing, personal struggles, and B-movie roles became a cautionary tale about the perils of talent without compromise. But this only adds to the mythic quality of his early work. It exists as a perfect, self-contained era of brilliance, a collection of performances that ask the eternal, haunting question: “What if?” The young Mickey Rourke was a comet that burned across the sky, and we are still captivated by the light he left behind.

Conclusion

The story of the young Mickey Rourke is one of the most compelling and tragic narratives in modern Hollywood. It is a story of unparalleled talent, of an actor who, for a short, glorious period in the 1980s, seemed to hold the keys to a new kind of cinematic kingdom. He was beautiful, gifted, intense, and utterly unique. From the smarmy charm of Teddy Lewis to the poetic weariness of The Motorcycle Boy, from the dangerous sensuality of John to the unraveling terror of Harry Angel, he created a gallery of characters that were as complex as they were unforgettable. His commitment to Method acting produced a level of authenticity that few actors have ever achieved, making every performance a raw, nerve-shaking event. He was not just playing roles; he was bleeding for them. The legacy of the young Mickey Rourke is forever etched in film history, a brilliant reminder of a promise that burned too bright and too fast, leaving behind a body of work that continues to inspire, unsettle, and amaze.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Young Mickey Rourke

What was Mickey Rourke’s breakout role?

While he had a small but memorable part in “Body Heat,” Mickey Rourke’s true breakout role is widely considered to be Robert ‘Boogie’ Sheftell in Barry Levinson’s “Diner” (1982). This performance showcased a stunning range, allowing him to transition from the slick criminal of his earlier role to a charming yet deeply vulnerable golden boy. It was this role that demonstrated his ability to convey complex inner turmoil beneath a cool exterior, signaling to critics and audiences that a major new talent had arrived. The performance was a masterclass in subtlety and made the young Mickey Rourke a name to watch.

How did Mickey Rourke prepare for his role in “Rumble Fish”?

The young Mickey Rourke’s preparation for “Rumble Fish” was a testament to his deep commitment to Method acting. To become The Motorcycle Boy, he worked extensively with director Francis Ford Coppola to understand the character’s philosophical, world-weary nature. He mastered a still, almost silent physicality, using his posture and gaze to convey a sense of mythic detachment. Rourke also reportedly learned to play the harmonica expertly for a specific scene, despite it not being a major part of the film. This total immersion, both physically and psychologically, was typical of his process and resulted in one of the most iconic performances of his early career.

Why did Mickey Rourke’s career decline after such a promising start?

The decline of the young Mickey Rourke’s career was due to a perfect storm of factors. Firstly, he became notoriously selective, turning down a string of blockbuster roles that would have cemented his A-list status. Secondly, his intense Method approach and uncompromising nature on set earned him a reputation for being difficult to work with, leading many directors to hesitate before hiring him. Most significantly, he made the conscious decision to leave acting in the early 1990s to pursue a professional boxing career, a move that was physically damaging and professionally alienating. This combination of artistic stubbornness, personal demons, and a deliberate step away from Hollywood led to the decline of his once-flourishing career.

What is Mickey Rourke’s most iconic film from his early period?

While there are several contenders, many critics and fans point to Alan Parker’s “Angel Heart” (1987) as the most iconic and complete performance from the young Mickey Rourke. In this psychological horror-noir, he plays Harry Angel, a private investigator whose journey into a voodoo-infused mystery becomes a slow descent into hell. Rourke’s performance is a brilliant arc, starting with cynical bravado and gradually crumbling into sheer, unadulterated terror. It perfectly encapsulates his unique ability to blend tough-guy charisma with profound vulnerability, making it a definitive showcase of his talents during his peak years.

How did Mickey Rourke’s boxing background influence his acting?

Mickey Rourke’s youth boxing background was fundamental to his entire screen persona. It provided him with a physical authenticity and a street-tough swagger that was impossible to fake. He moved like a fighter—with a certain grace and a palpable sense of danger. This history gave his characters a lived-in quality; when he played hustlers, gangsters, or men on the edge, the audience believed it because he had genuinely come from that world. The discipline, pain, and solitary nature of boxing also paralleled his approach to acting, which he treated as a grueling, all-consuming discipline. Ultimately, this same background also pulled him away from acting, as he felt a need to return to the ring, a decision that directly impacted the trajectory of his stardom.